Three weeks ago, I embarked on a six-month study to establish a program, scope, and cost for a new annex at Swedenborg Chapel, to replace the aging and deteriorating 1965 addition along Kirkland Street. As an architecture student at the Harvard Graduate School of Design in the late 1990s, I would walk past this quiet, enigmatic chapel on a daily basis, and I always wondered why it was called “Swedenborg” Chapel. And what about the Swedenborg Library, announced by a tiny sign in one of the large plate-glass windows of the 1960s addition? I knew of some fellow students who were married in the chapel toward the end of my time at the GSD, but I never found an opportunity to take a look inside.

A few years later, I was settling into my career as a young intern-architect working with Tom Payette, founding principal of Payette Associates, a Boston firm specializing in buildings for health and science. Tom, now retired, is a 1960 graduate of the GSD, which at the time was housed in Harvard Yard in Robinson Hall. During one of our many trips to New York Medical College, he mentioned having worked full-time during graduate school and noted that I was probably aware of the architect he worked for, Arthur Brooks. “You know that chapel next to the GSD, Swedenborg Chapel?” he asked. “Arthur Brooks was the architect of the little addition on the Kirkland Street side.” Yep. I knew what Tom was talking about.

When my wife and I were looking for a venue for our wedding, we quickly homed in on Swedenborg Chapel. It was a natural choice given we had both been longtime residents of Cambridge and were planning to have a fairly small and intimate ceremony. Five years later we returned to attend Sunday services, drawn to the chapel’s ethereal quality and, increasingly, the mystical and deeply spiritual nature of Swedenborg’s vision of Christianity. These personal intersections with Harvard and Swedenborg Chapel are indicative of a much larger story of how these two institutions rubbed shoulders numerous times over the past 100+ years. As part of my study, I have just begun to scratch the surface this history, and the intersections so far are fascinating – a reminder that “nothing unconnected ever occurs.” 1

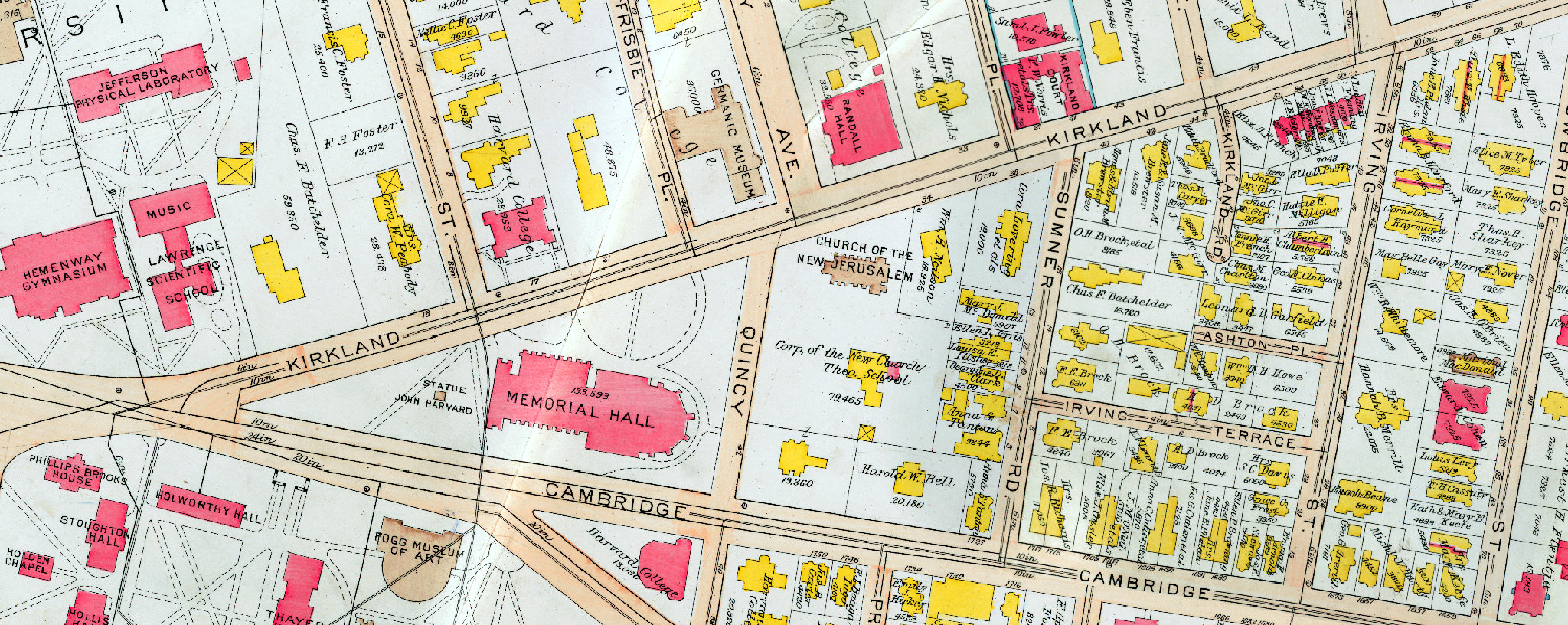

Period plan of Harvard and Cambridge from 1865 – see footnote 13 for source. Swedenborg Chapel will be built where “Prof Lovering” is written, just below “Kirkland St.”

According to historian Maureen Meister, the Cambridge Society of the New Jerusalem – the formal name of the congregation that worships at Swedenborg Chapel – was formed in 1888.2 The following year, the New Church Theological School purchased the Treadwell-Sparks house at 48 Quincy Street, directly south of the site where the chapel would later be built in 1901. Named for Jared Sparks, professor of ancient and modern history and president of Harvard (1849-53), the Treadwell-Sparks house would become the home of the school. Ten years later, planning commenced for the chapel, which would serve both the congregation and the school.3

The chapel’s architect was Herbert Langford Warren, a prominent Boston architect among whose many accomplishments include being the founder and president of the Society of Arts and Crafts, Boston and the first “dean of the School of Architecture at Harvard, having taught there continuously since offering the first course in architecture in 1893.” 4 Warren was a lifelong practicing Swedenborgian, influenced by his father’s commitment to the faith.5 Meister discusses Warren’s preference for English styles of architecture,6 and I wonder whether this stems from Warren’s English roots – he was born, reared, and educated in Manchester 7 – or from Swedenborgianism’s English roots – the church was founded in England in 1787 by devotees of Emanuel Swedenborg’s distinctive Christian theology 8 – or both. In any case, the chapel adopts an English gothic style “consistent with Warren’s deeply felt affection for the medieval English parish church, which he expressed to his students in his lectures. It is also consistent with the broader enthusiasm for the English architectural tradition that was prevalent in Boston during this period, when the Yankee population sought to affirm its Anglo-Saxon heritage.” 9

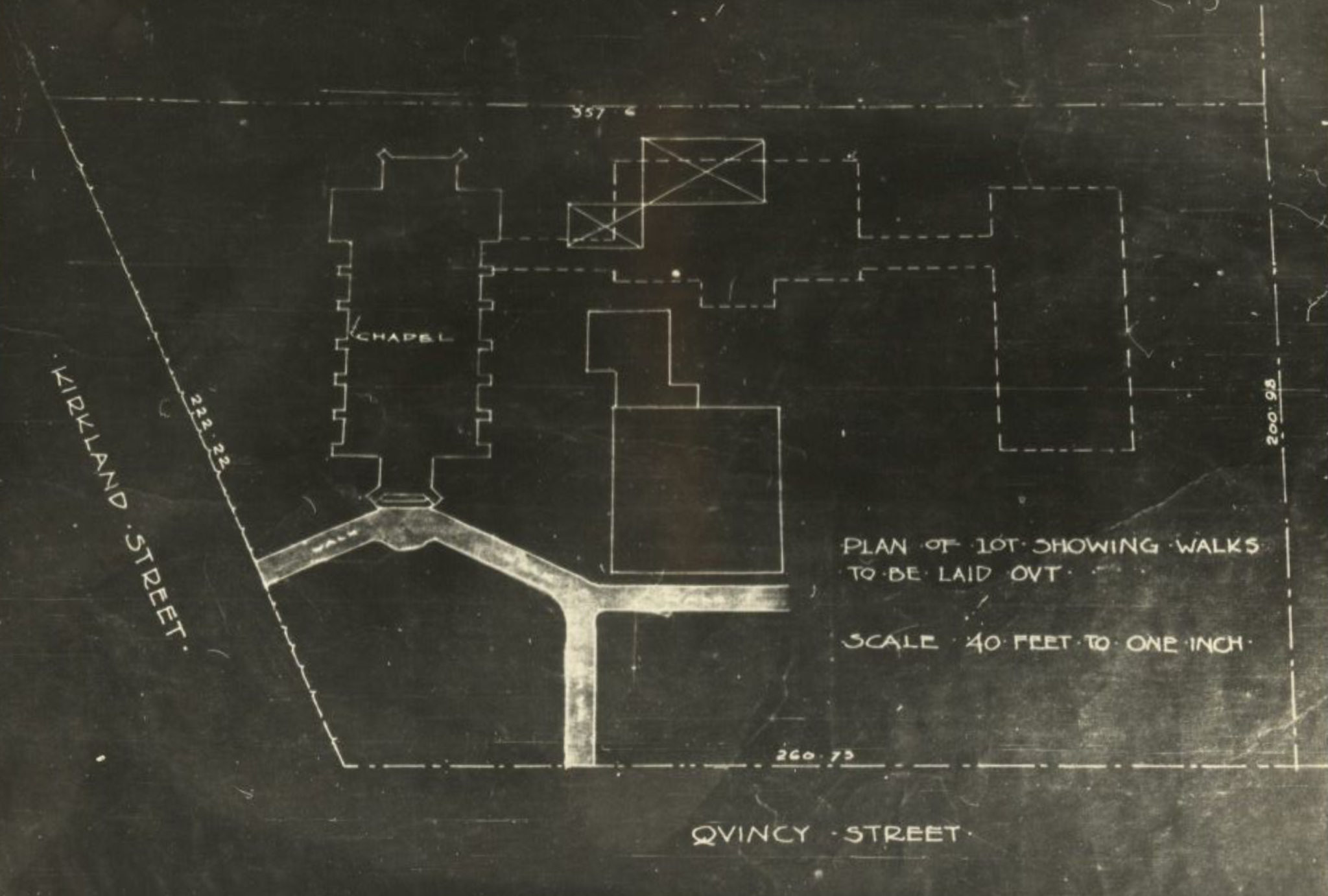

Undated site plan attributed to the firm of Warren, Smith & Biscoe – see footnote 10 for source. Note the dashed lines extending from the chapel behind Treadwell-Sparks House, suggesting a master plan vision for future development of 48-50 Quincy Street. North is roughly to the left.

The above undated site plan is attributed to Warren 10 and shows the chapel in relation to the New Church Theological School in Sparks House at 48 Quincy Street. In the 1960s, the school decided to relocate to Newton and sold the Sparks House property to Harvard. Given the historical significance of the house, Harvard relocated it a short distance away on Kirkland Street, where it remains today as the home for the minister of Harvard Memorial Church. As Robert Kirven observed in 1968,11 this was in fact the second time that Sparks House had been moved. Note how close it is to the chapel in the site plan above. As Cambridge preservation planner Sally Zimmerman notes, “in 1901, the house was turned 90 degrees and moved south on its lot to make room for the chapel’s construction.” 12 This can be seen in the following period plan from 1916: 13

Period plan from 1916 – see footnote 13 for source. Note how the Sparks House (labeled “Corp. of the New Church Theo. School”) is rotated and shifted south, away from the chapel (labeled “Church of the New Jerusalem”). Also of note: the nearby Germanic Museum, northwest of the chapel, is also a H. Langford Warren building.

The emergence of the New Church Theological School marks the beginning of a decades-long transformation of Quincy Street. Starting in the 1840s, Quincy Street began to unseat “Professor’s Row” (Kirkland Street) “as a prime residential location for those connected to [Harvard College], and it remained so up to the end of the 19th century, as a cosmopolitan group of noted academics settled along the street’s length.” 14 This can be seen in the 1865 period plan above, where five faculty houses were on the west side of Quincy Street, in Harvard Yard, eventually to be replaced by expansion of academic facilities, in particular, Robinson Hall, Sever Hall, and Emerson Hall.

Rotated and expanded view of 1916 period plan highlighting parcels along Quincy Street that would see radical transformation over the next 100 years. North is to the left.

By 2016, all of the homes along the east side of Quincy Street, extending south to the Harvard Faculty Club (“The Colonial Club” in 1916), would be replaced by (from north to south): Gund Hall, housing the Harvard Graduate School of Design at 48 Quincy Street (occupying both 42 and 48 Quincy); the Arthur M. Sackler Museum (between Broadway and Cambridge Street); the Fogg Museum of Art (now the consolidated Harvard Art Museums, recently expanded in 2015 by Renzo Piano Building Workshop and Payette); and the Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts. The transformation began with the Fogg Museum, designed by architects Coolidge, Shepley, Bullfinch, and Abbott of Boston and built in 1927, taking over 28-36 Quincy Street.15 In 1963, the Le Corbusier-designed Carpenter Center was completed, with its iconic ramp structurally integrated with a basement book stacks facility that was added to the back of the Fogg in 1961 to expand the Fine Arts Library.16 The last piece of the transformation was construction of the Sackler Museum in 1985,17 replacing the 1951 Allston Burr Lecture Hall,18 an outdated science building that had supplanted two smaller residential buildings for Harvard College, shown in the 1916 period plan. And it was in 1969 that work began at 48 Quincy Street to construct Gund Hall for the Harvard Graduate School of Design (“GSD”), bringing the school that Herbert Langford Warren had founded in the late 1800s directly next door to the chapel he designed for his fellow Swedenborgians and affiliated theological school. A few years earlier in 1963, the Minoru Yamasaki-designed William James Hall was completed to house Harvard’s Department of Psychology, which William James was instrumental in establishing.19 James’ father, Henry James, Sr., was deeply influenced by the writings of Emanuel Swedenborg.20

2018 period plan showing the transformation along the east side of Quincy Street. North is to the left.

By the time it relocated to Newton in the 1960s, the New Church Theological School changed its name to the Swedenborg School of Religion 21 (“SSR”), and the school built an annex on the north side of the chapel, facing Kirkland Street. Designed by Cambridge architect Arthur Brooks, it provided fellowship space and other ancillary functions to support the Cambridge Society congregation, which continued to hold services at the chapel after the school’s departure. By the late 1990s, SSR announced its intentions to sell the chapel property to raise much-needed capital to support its operations. Concerned about the potential loss of a significant work of architecture, the local community and the Cambridge Historical Commission lobbied successfully to obtain City of Cambridge landmark status for the chapel and paving the way for the Massachusetts New Church Union and the Cambridge Society to purchase the property from SSR in 2001.22 Harvard continues to hold a right of first refusal for 50 Quincy Street, the only parcel of land that Harvard doesn’t own on the block bounded by Quincy Street, Kirkland Street, Sumner Road, and Cambridge Street. The GSD recently announced it is undertaking a master plan for its current facilities, and one has to wonder whether the land-hungry university is eyeing the chapel and its grounds.23 The Union and the Society are in charge of a sacred trust to conserve this special place into the next century, and it’s an honor to be trusted to guide the process.

Period plans from 1947, 1969, and 2018, showing the triangulation over time of Swedenborg Chapel, Sparks House, and the Harvard Graduate School of Design. In the 1969 plan, note the swath of land that bears the trace of the Sparks House relocation.

Notes:

1 Emanuel Swedenborg, Arcana Coelestia 2556. See https://swedenborg.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/swedenborg_foundation_arcana_coelestia_03.pdf for the older translation, “… anything unconnected is impossible … .”

2 Maureen Meister, Architecture and the Arts and Crafts Movement in Boston: Harvard’s H. Langford Warren, (Lebanon, NH: University Press of New England, 2003), 110.

3 Ibid.

4 Ibid., 1.

5 Ibid., 7-8.

6 cf. Meister, 5, 110.

7 Meister, 8.

8 Ibid.

9 Ibid, 110. This idea of how architecture can be a cipher for asserting cultural or racial identity is an interesting and challenging issue that will doubtless come up again in a future article.

10 Misako Akutsu, John Robinson, and Laurence Williams, Church of the New Jerusalem, Unpublished student report for Professor Eduard Sekler, Harvard University Graduate School of Design, 1974, 15-16.

11 Robert H. Kirven, “Letter from the Editor,” The Messenger 188, no. 10 (October 1968): 142-143.

12 Sally Zimmerman, “Church of the New Jerusalem / Swedenborg Chapel, 50 Quincy Street, Landmark Designation Study Report,” Unpublished report prepared for the Cambridge Historical Commission, March 5, 1999, 8.

13 Period plans developed from City of Cambridge MA GIS Historical Viewer, https://www.cambridgema.gov/GIS/interactivemaps/Cambridgecityviewer (February 7, 2019).

14 Zimmerman, 8.

15 https://www.harvardartmuseums.org/about/history-and-the-three-museums (February 7, 2019).

16 https://carpenter.center/building/architecture (February 7, 2019). I also conducted research on the history of the Fogg and the Fine Arts Library in 2006 for an unpublished report for Harvard University.

17 https://www.harvardartmuseums.org/about/history-and-the-three-museums (February 7, 2019).

18 Susan E. Maycock and Charles M. Sullivan, Building Old Cambridge: Architecture and Development, (Cambridge MA, The MIT Press, 2016), 817. Allston Burr was designed by architect Jean-Paul Carlihan of Coolidge, Shepley, Bullfinch & Abbott.

19 https://cambridgehistory.org/james/James%205.html (February 7, 2019).

20 https://swedenborg.org/famous-swedenborgians/henry-james-sr/ (February 7, 2019).

21 “Swedenborg Chapel owners can wait no longer,” Cambridge Chronicle, date unknown, accessed from the Frank Patterson Smith collection at Historic New England.

22 The school is now in Berkeley, CA, and is operating as the Center for Swedenborgian Studies of the Graduate Theological Union. CSS is the seminary of the Swedenborgian Church of North America, which has its central office at 50 Quincy Street, Cambridge.

23 “Harvard GSD selects Herzog & de Meuron, Beyer Blinder Belle for transformative expansion of School’s Gund Hall,” https://www.gsd.harvard.edu/2018/07/harvard-gsd-selects-herzog-de-meuron-beyer-blinder-belle-for-transformative-expansion-of-schools-gund-hall/ (February 9, 2019).